Five Percent Defense Spending: An Opportunity or a Threat to Czech Finances?

Within NATO, Czechia has committed to gradually increasing its defense spending to "five percent" of gross domestic product by 2035. While the law on defense financing currently requires it to spend at least two percent, the new commitment represents a leap that would mean hundreds of billions of crowns extra. The question is whether Czech public finances can bear this burden and what sacrifices will have to be made in other areas of the state budget.

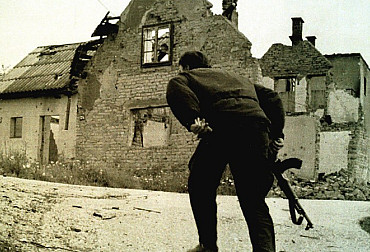

The debate on increasing defense spending has been going on for a long time in Czechia. However, recent years, marked by the war in Ukraine and generally growing tensions in the world, have brought about a fundamental change: the former effort to "meet allied commitments" within the framework of NATO's two percent target is becoming a much more ambitious task. At the alliance summit in The Hague, member countries pledged to spend "up to" five percent of GDP on defense and related activities by 2035. For Czechia, this presents a completely new dilemma. Given the current size of the economy, spending would rise from around CZK 160 billion to between CZK 280 billion (3.5%) and CZK 400 billion (5%). In other words, the army and defense would account for up to a fifth of all government spending. And this at a time when the state budget is already suffering from a chronic deficit and cannot do without annual borrowing, which entails growing costs for servicing the debt itself.

Context and commitments of Czechia

Current Czech legislation – specifically the 2023 Defense Financing Act – requires the government to allocate at least two percent of GDP to the military. For a long time, this target seemed to be the maximum possible, as Czechia only managed to meet it last year. However, it now appears that this is only the beginning from NATO's perspective. At the alliance's summit in The Hague in June, member states committed to allocating five percent of GDP to defense and related activities by 2035. The structure of this figure is key: purely military spending is to account for 3.5 percent, while the remaining 1.5 percent covers a broader concept of security—for example, investment in infrastructure that can also be used by the military, state material reserves, or crisis management.

In the Czech Republic, this commitment is divided into stages. The government has already decided that by 2030, spending will increase by two-tenths of a percentage point of GDP each year, so that by the end of the decade it should reach at least three percent. Only then will the remaining part come into play. This gradual increase is necessary not only because of the budget, but also because the Czech defense industry and army are not able to immediately absorb such a high influx of money. A sudden increase would lead to market overheating, a sharp rise in equipment prices, and possibly inefficient spending. The five percent commitment is therefore not just a matter of numbers. It is a strategic decision that will determine how large an army Czechia can afford, what role it will play in NATO, and how the state budget as a whole will change. And it is precisely the budgetary aspect that raises the most questions.

Financial dimension: Hundreds of billions extra

From the perspective of the state treasury, increasing defense spending from the current two percent to five percent of GDP represents a significant leap. This year, two percent of GDP amounts to approximately CZK 160 billion, which corresponds to just under eight percent of all budget expenditures. This amount is already the highest in the history of the independent Czech Republic. However, if the state were to start fulfilling its Hague commitment today, it would mean spending between CZK 280 and 400 billion per year, depending on whether it was 3.5% or the full 5%. Such sums would represent 13 to 19 percent of all state budget expenditures. In other words, almost every fifth crown spent by the state would go to the army and "dual-use" projects.

Economists point out that such high expenditures are not merely an accounting item, but a fundamental political and social decision. The Czech budget is already struggling with a chronic structural deficit. This means that even without extraordinary expenditures, the state spends more than it can collect in taxes in the long term. For this reason, a sharp increase in defense spending could not be financed without radical measures—whether in the form of tax increases, cuts in other areas, or continued borrowing. It should be emphasized that five percent of GDP is the target for 2035. This means that Czechia will have more than a decade to gradually increase its budget, prepare its defense industry, and seek savings in other areas. The problem remains, however, that time alone will not solve the structural weaknesses of public finances. Without reforming expenditures and revenues, even a gradual increase will reach its limits.

Fiscal impacts

The idea of "five percent" defense spending cannot be implemented in budgetary practice without specific measures that the government would have to adopt. There are basically three main scenarios—each with its own advantages and disadvantages, and all of which will have an impact on the lives of citizens to some extent. The simplest but most politically sensitive solution is to increase state budget revenues. This would mean higher VAT rates, the abolition of certain tax exemptions, or more progressive taxation of individuals and legal entities. In practice, this would lead to defense costs being spread across all citizens and businesses. However, tax increases could hamper economic growth and weaken the competitiveness of the Czech economy, especially if neighboring countries did not take similar steps.

An alternative is to redirect funds from other areas. The most frequently discussed options are cutting spending on social benefits, pensions, subsidies, or infrastructure investments. However, this approach is extremely risky politically, as it would provoke voter resistance and social tension. Cuts to the pension system, for example, would directly affect millions of people, which could undermine the legitimacy of the decision to strengthen the army. The third option is to finance the increased spending through debt. Although the Czech Republic's debt is lower than the eurozone average, its growth rate is among the fastest. If the government relied mainly on loans, this would mean higher debt servicing costs and less flexibility in crisis management in the long term. Every additional billion in interest would then be missing elsewhere—whether in education, healthcare, or social services.

In reality, the government would have to take a combined approach: partially increase taxes, partially cut other spending, and cover part of the costs with debt. The question remains, however, whether the Czech political system is capable of pushing through such an unpopular compromise in the long term. The experience of recent years shows that consensus on structural reforms is exceptional in Czechia. In conclusion, it can be said that the commitment of up to five percent of GDP to defense represents a double-edged challenge for Czechia. On the one hand, it is an opportunity to fundamentally modernize the army, strengthen the defense industry, and consolidate our position within NATO and European security. On the other hand, however, it cannot be overlooked that this is an extremely demanding financial goal that will affect all areas of the state economy. The Czech economy and political leaders will therefore have to strike a balance between security commitments and sustainable public finances. The key will be whether it is possible to implement a long-term strategy that combines a gradual increase in spending with reforms on both the revenue and expenditure sides of the budget. Without these, even a well-intentioned commitment could become more of a threat than an opportunity.