Three years of support for Ukraine: What the outgoing Czech government leaves behind

Petr Fiala's coalition government is preparing to step down. Its steadfast support for Ukraine is one of the most significant legacies of the past election period. In the context of Europe, where war fatigue is becoming a clear political and social phenomenon, the Czech Republic has emerged as the main Central European driver of support for Kyiv. The result of this political line has been extensive military and economic aid, accompanied by an exceptionally strong position for the Czech defence industry. However, this position is taking on a different dimension following Andrej Babiš's appointment as head of the new government. The changing geopolitical atmosphere and growing Euroscepticism are creating an environment in which the Czech Republic's stance on Ukraine may become a test of domestic political courage and the ability to maintain strategic continuity.

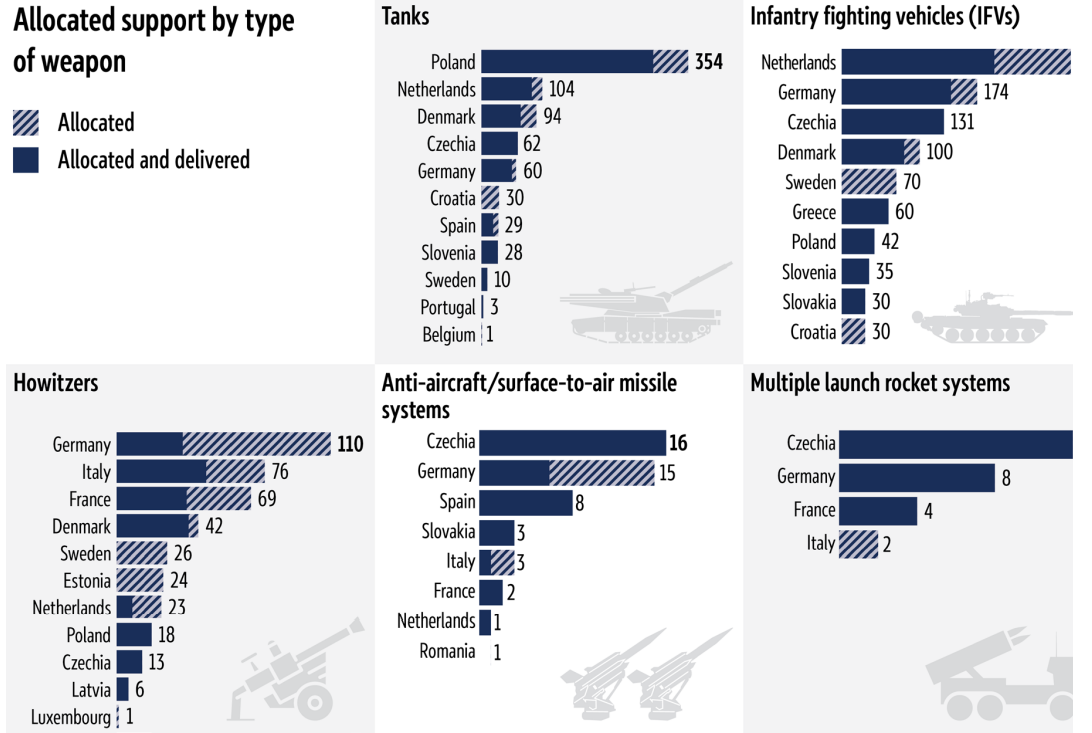

According to an October report by the Czech Ministry of Defence (MO), Czech military aid to Ukraine has reached a total value of CZK 17.4 billion since 2022. This sum includes donations of equipment, ammunition, financial contributions, and training programs. At the same time, Prague received approximately CZK 25 billion from refunds and European sources, so the resulting balance remains positive. Support for Ukraine was therefore not a unilateral financial expenditure, but an economically rational step that contributed to the development of the domestic defence sector. Over the course of three years, this sector has created over 2,600 jobs and plans to invest over CZK 15 billion by 2030. The Ministry of Defence also emphasized that Czech companies have brokered deliveries of military equipment to Ukraine worth more than CZK 260 billion, financed mainly by foreign partners. Such extensive involvement has transformed the Czech defence industry from a regional player into one of European significance.

"There has been a lot of inaccurate and misleading information circulating in the public sphere recently about the Czech Republic's military aid to Ukraine, with representatives of the emerging coalition using nonsensical figures to justify their intention to stop our aid to the attacked country. The end of the government's term of office is an opportunity to take stock, and we have therefore decided to summarize and quantify everything we have done in terms of military support for Ukraine," said Defence Minister Jana Černochová. She added that the time was right for an open assessment of the results, which had long been kept secret for security reasons. The assessment thus also serves as a political manifesto: the defence of Ukraine is not a charitable act, but part of the Czech Republic's security strategy.

The Czech ammunition initiative, coordinated with alliance partners (e.g., Denmark, Canada, and the Netherlands), became a central element of this strategy. It secured over 3.7 million pieces of large-caliber artillery ammunition for Ukraine. The United States even asked the Czech Republic to take over the leadership of the so-called Ammunition Syndicate and thus become the main coordinator of all Western supplies of artillery ammunition to Ukraine. This effort strengthened Prague's position as a reliable coordinator and demonstrated the Czech side's ability to translate political commitments into concrete material support. According to the Ministry of Defence, Czech supplies helped change the ratio of artillery fire from ten to one in Russia's favor to two to one, which had a direct impact on stabilizing the front line during 2024.

At the European level, war fatigue and pressure on public budgets are becoming increasingly apparent. The German Kiel Institute recorded a sharp decline in military aid during the summer of 2025, despite commitments made at previous NATO summits. At the same time, it appears that Europe, not the United States, is now becoming the main pillar of Ukrainian financing. Team Europe has provided Ukraine with €173.5 billion in support, of which €63 billion is for military supplies. These figures demonstrate an extraordinary degree of solidarity, but also the limits of the European model, which is based primarily on loans and temporary budget transfers. Within this framework, the Czech Republic is one of the countries that has fulfilled its military aid commitments in full and has not postponed its obligations, which stands in stark contrast to some Western European supporters.

In a recent interview with the French daily Le Monde, President Volodymyr Zelensky stated that Ukraine will need European support for another two to three years. This statement is not only an estimate of the duration of the conflict, but also a warning. An interruption in the flow of financial and material aid could mean a major turning point on the front lines and in Ukrainian society. At the same time, Zelensky called for the use of frozen Russian assets either to rebuild the country if the war ends soon, or to purchase weapons if the conflict continues. In doing so, he sent a double message to Europe: the time frame for support remains finite, but its intensity will determine whether Ukraine can hold out until the end.

In this context, the Czech Republic's approach serves as an example of realistic solidarity. Unlike other countries, Prague did not place excessive expectations on its aid to Ukraine, but instead systematically developed the capacities of domestic industry and alliance coordination. The result has been political capital and concrete economic effects, from export contracts to new jobs in regions where CSG, STV Group, PBS Group, and Colt CZ operate. The Czech Republic's role as an intermediary between Western donors and Ukrainian needs has brought the country international recognition, but also a certain dependence on the continuation of European solidarity. If the Union's financial unity were to be disrupted, the Czech strategy would lose its support and the current model of support would be at risk of collapse.

Andrej Babiš's new government will face this risk immediately after taking office. His pre-election rhetoric, which ranged from emphasizing peaceful diplomacy to criticizing the long-running war, suggests a more pragmatic Czech approach and a less ideologically driven direction. The question remains as to how compatible such a policy will be with European commitments. While allies such as Germany and Denmark are willing to continue their assistance, other countries are reevaluating their position. Slovakia, under new leadership, has almost halted its supplies, Hungary rejects new financial mechanisms, and Poland faces cheap imports from Ukraine (steel, cement). The Czech Republic will either maintain the symbolism of solidarity that has earned it respect in NATO and the EU, or it will join those who are relativizing their support for Kyiv.

The situation is further complicated by the state of European financing, as more than three-quarters of European aid to Ukraine takes the form of loans. In the long term, Kyiv will therefore be dependent on the EU's ability to maintain the mechanism for repaying interest on frozen Russian assets. However, as The Economist points out, these funds will not cover even half of the expected needs, with a shortfall of around €230 billion. Without a common European debt instrument or more significant national contributions, Ukraine risks hitting its financial ceiling in 2026. It is at this point that it will become clear whether Europe, including the Czech Republic, sees the war as a matter of existence or merely as an episode in foreign policy.

At the NATO summit in Washington in 2024, the allies pledged to provide Ukraine with military equipment worth €40 billion this year, which for the Czech Republic means approximately CZK 6.4 billion. According to a report by the Ministry of Defence, this commitment has been fulfilled in full. The Czech army provided Kyiv with a total of 390 pieces of surplus equipment, ranging from tanks and howitzers to helicopters, and arranged for the delivery of ammunition from domestic and foreign sources. In terms of alliance solidarity, Prague has stood its ground. However, this will not be a matter of course for the new government, as each additional year of war brings new budget priorities, pressure on domestic investment, and growing public discontent.

Minister Černochová therefore saw her final report not only as statistics, but also as a warning. According to her, ending Czech involvement would have very serious consequences for Ukraine. In three years, Czech support has become a system that shapes the balance on the battlefield and trust among allies. Stopping this mechanism would threaten not only Kyiv, but also the Czech Republic's own position in the Euro-Atlantic space. At a time when the United States has reduced its financial aid following the election of Donald Trump as President and Europe is grappling with disagreements over the confiscation of Russian assets, continuity is becoming extremely valuable.

Zelensky's words about two to three years therefore resonate in Prague as well. They represent a realistic time frame that could be decisive for Ukraine and for Europe's credibility as a geopolitical actor. If the Czech government can convince the public that defending Ukraine also means protecting Europe and the Czech security space, it can maintain its strategic line regardless of the political color of the cabinet. However, if domestic political populism and economic calculations prevail, there is a risk that the Czech balance sheet will turn from a success story into an epilogue of a lost opportunity.

The outgoing government leaves behind a solid framework of military, economic, and diplomatic support that has brought prestige and tangible results to the Czech Republic. Its strategy has combined moral imperatives with economic realities and created a model that has inspired other European countries. What began as a spontaneous response to aggression has evolved into a well-thought-out system in which security and economic interests are combined. The coming years will determine whether this system will become the basis for long-term policy or merely a chapter in the history of Czech foreign policy.