Lubor Koudelka: We are not hindering military procurement, but guaranteeing its legality and transparency

The processes of procuring military equipment and systems in Czechia are often criticized due to the length of time these acquisitions take. However, according to Lubor Koudelka, former Director General of the Armament and Acquisition Section of the Czech Ministry of Defense (SVA MO), most of the criticism is unjustified, as the acquisition process must comply with the Public Procurement Act, a number of government regulations, and internal ministry regulations. In an interview, Lubor Koudelka describes how the Ministry of Defense is striving to speed up procedures through digitization and amendments to internal guidelines, how rising inflation and demand for military equipment are increasing prices by more than 10 percent annually, and why purchases – such as Leopard 2A8 tanks – cannot simply be compared with other NATO countries. He also explains that media pressure for transparency in procurement is leading to a higher administrative burden and that the biggest obstacle to effective acquisitions today is not bureaucracy, but a lack of qualified personnel.

The length of acquisition processes in the Czech Republic is often criticized as being too lengthy. What do you think often slows down their implementation?

First and foremost, it must be noted that this criticism is very often unjustified and that in many cases the delays are not caused by the Ministry of Defense. First and foremost, it is important to realize that in acquisitions, we must comply with the provisions of the Public Procurement Act and a number of other laws and government regulations that require a whole range of administrative steps and set minimum deadlines for their implementation. In addition, there are internal ministry guidelines aimed at ensuring the management and control of acquisition processes. The vast majority of contracts handled by the SVA MO are above-threshold in nature, and we have calculated that, for example, an above-threshold open procedure will take at least 275 days from receipt of the request, assuming there are no delays, while an above-threshold restricted procedure requires at least 322 days, and the tendering procedure for exceptions to the law takes at least 330 days. In many cases, however, delays occur, for example, because potential suppliers require additional information, and competition also plays a role, with bidders sending objections and sometimes even filing complaints with the Office for the Protection of Competition. Such complaints can delay the acquisition by six months or sometimes even longer.

Another problem is the specificity of the materials and services we procure, where it is not uncommon for no bidders to apply, or for bidders to be excluded for failing to meet the conditions, and the acquisition process must be repeated with adjustments to the parameters of the requested materials.

The procurement of complex and technically demanding systems is a separate issue, where, for example, aligning our technical and operational requirements with the manufacturer's actual ability to deliver them can significantly prolong contract negotiations. At the same time, the specifics of procuring such systems from abroad – whether directly from the manufacturer or at the government-to-government level – also have a significant impact here.

There are certainly other factors, such as delays in deliveries due to the removal of defects found during prescribed tests, quality control, supplier delays, and the like. It is important to note that significant delays in acquisitions carried out by the SVA MO are in fact rather exceptional, and we fulfill most acquisition requests within the required deadlines, even though some may seem long.

What specific steps is the SVA taking to speed up the tendering and approval procedures?

We have been working intensively on this issue for several years and will continue to do so. However, it is clear from the above list of various causes of delays that the Ministry of Defense can only influence some of them. For example, our options are limited in the area of legislation, because the Public Procurement Act is a transposition of European directives, but we have nevertheless managed to achieve partial changes in our favor. We have also managed to simplify some of the administrative processes required by government regulations.

The Ministry is focusing primarily on amending our internal regulations to reduce administrative burdens and simplify processes with the aim of speeding them up. We continuously evaluate the experience we have gained, analyze processes, look for bottlenecks, and seek possible remedies. We have also started work on digitizing processes, which should also contribute to shortening deadlines, especially in the preparatory phase of acquisitions.

Do long acquisition processes lead to higher costs for the purchased equipment? If so, how much higher?

Of course it does. This trend has always been there, but it became more pronounced after the COVID-19 pandemic due to inflation and, in particular, after Russia's aggression against Ukraine. Demand for military equipment and materials has risen sharply, to which manufacturers have naturally responded by raising prices, but input prices, including raw materials and semi-finished products, have also risen significantly due to their scarcity.

It is impossible to say how much this amounts to, as it varies from case to case, but a very rough estimate is 10 percent per year, and in many cases even more. Today, it is quite common for multi-year supply contracts to include a so-called inflation clause reflecting the expected price increases over the years. Without such a clause, suppliers are often unwilling to enter into a contract at all.

How is the section coping with rising prices of military equipment due to inflation, market changes, or geopolitical tensions?

The Armament Section does not manage financial resources; their planning is the responsibility of the user, which in the vast majority of cases is the Czech Armed Forces, in cooperation with the Economic Section. It is the user's responsibility to conduct initial market research, determine the estimated value of the contract, and plan financial resources accordingly.

The Armament and Acquisitions Section is responsible for updating these surveys before the acquisition begins. If we find that the original estimate is no longer accurate, the user must decide whether they are able to secure more funds or change their requirements for the quantity or design of the requested material. The final price is, of course, only known after negotiations with the potential supplier have been completed. One of the important steps we take in cases where there is no competition is, of course, to verify whether the price is customary or market price in order to prevent the contract from being overpriced. The most basic rule in this area is that we cannot execute a public contract, including the conclusion of a contract, unless its financing is secured.

To what extent is the life cycle of equipment, including operating, maintenance, and modernization costs, taken into account when planning purchases?

I must admit that we have room for improvement in this area. Life cycle cost estimation is a legally permissible indicator of the economic viability of a contract, but the ministry has very limited capacity to perform these estimates. For this reason, they are only used for essential types of military equipment. How and to what extent the life cycle of the acquired assets will be secured and how it will be financially secured is not the responsibility of the SVA MO, but primarily of the user. The user must take this into account in their planning and, if it requires any acquisitions, such as a service contract, the purchase of spare parts, ammunition, and the like, they must plan this acquisition, secure it financially, specify specific requirements, and we will then ensure the implementation of such acquisitions.

As the Ministry is aware that we have reserves in this area, work is underway to create capacities and set up a system and corresponding processes for comprehensive life cycle management. This is a very demanding task, the implementation of which will take some time.

Does the Czech Republic purchase at comparable prices to other NATO countries, or do you see certain differences? If so, why?

This question is difficult to answer. In cases where we know the purchase prices of similar materials, the answer is basically yes. It is not possible to give a clear and specific answer for several reasons. The simpler reason is that the prices of these contracts are usually not known, and if they are, it is the price of the contract and the prices of individual items and the complete list of what the acquisition includes are definitely not published. This can lead to apparent differences in the price of similar material for foreign customers and for us.

The second, more complex reason is that in the field of military technology, it is not common for every country to purchase a uniform design, but rather to apply a whole range of national requirements to the technical design. This, of course, significantly affects the final price, as more changes mean a more expensive design. An example of this is the purchase of the Leopard 2A8 tank, where we purchase the base model at the same price as Germany, but due to the need for so-called "Bohemization," i.e., different communication and information systems, the manufacturer must technically adapt the tanks for the Czech Republic, which may result in a certain increase in price. The time when the technology was purchased also plays a role, both because of year-on-year price increases and because the days when some suppliers were happy to take any order are gone. Today, they are almost certain that if they don't sell it to us, someone else will buy it, and they can dictate prices to a certain extent. These are some of the reasons why it is often very difficult to determine the usual or market price.

How much pressure does the need for rapid rearmament of the army exert on you in the context of the current security environment?

The pressure is quite considerable; for example, between 2022 and 2024, we successfully carried out a number of urgent purchases. The need for rearmament has been discussed for many years, but this requirement has not been covered by the necessary financial resources. The enactment of defense spending at 2 percent and its further gradual increase has enabled us to launch a number of strategic and particularly important projects. This involves technology that is complex, expensive, and often only available from foreign suppliers. The implementation of each such acquisition means a significant increase in administrative, time, and therefore personnel demands. The number of people involved in such acquisitions is much higher than for ordinary acquisitions. Whereas in the case of ordinary acquisitions, for example, one contract manager, in cooperation with a lawyer, was able to handle several contracts a year, in the case of such a demanding contract, he or she is unable to perform other tasks, often for several years. For us, the main problem is the lack of qualified and experienced personnel, mainly because there are not many such people on the labor market and salaries in the civil service are not very competitive. Fortunately, the budget increase due to the implementation of financially demanding acquisitions did not result in a large increase in the number of requests in the calendar year, otherwise we would have been forced to postpone some less important acquisitions due to capacity reasons.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of purchasing through intergovernmental agreements compared to open competitive bidding?

Competition is generally considered the best way to achieve the most favorable price, which is not always the case, especially when competition in the market is very limited. Unfortunately, this is true in many cases for the materials we purchase. There is also a risk that potential suppliers may agree on a price, for example. There are cases where someone submits a lower price, but the other potential suppliers already expect to become subcontractors or similar. The contracting authority's options for uncovering this are quite limited. In addition, there is always the risk of objections being lodged, complaints being filed with the Office for the Protection of Competition, and the like in the context of competition, which always delays and increases the cost of the acquisition, and sometimes even thwarts it.

The main advantage of an intergovernmental agreement, i.e., a government-to-government purchase, is that the acquisition is always guaranteed by the government of the country concerned, even though the supplier is, of course, in the vast majority of cases a specific manufacturer. It is assumed that this guarantee will ensure the proper performance of the contract and all other related obligations. The disadvantage is that few countries are willing to enter into such an acquisition, some are not even allowed to do so by national legislation, and there are few commodities that can be procured in this way.

Does increased public and media pressure for transparency in procurement increase administrative burdens and prolong processes? If so, how do you address this?

The increase in requests for information has risen significantly in the last six months, but interest from the media and the public is relatively constant. It is not unusual for companies to use the Freedom of Information Act in the context of competition, when they ask for very specific and concrete information.

In accordance with the law, we try to comply with these requests, which is our duty, but each such request means an increase in the administrative burden, because we have to assign a relevant employee to process the response instead of having them focus on their tasks directly related to the implementation of defense acquisitions. In many cases, this takes up a lot of time, perhaps at the expense of the contract on which they are working. While this does not cause any significant delay to the contract, it is extra work. However, in accordance with the law, we would charge a fee for requests that are very time-consuming and require the work of a large number of people. In such cases, applicants usually revise their requests to a level that does not require payment.

Do you see decentralization of procurement powers, for example towards individual branches of the armed forces, as a solution for greater flexibility in the future?

First and foremost, SVA MO is not the only procurement department within the Ministry of Defense. For example, real estate infrastructure is handled by the Ministry of Defense's property section, while other procurements are carried out independently by the Military Police, the logistics section, the communications and information systems section, and small-scale contracts by individual departments or units within the Ministry of Defense.

Decentralization as a suitable way to reduce the workload of the main procurement departments, such as the SVA MO, was identified and implemented several years ago, when, for example, some contracts worth up to CZK 100 million were awarded by logistics agencies or the KIS. This process continues, and a practice is currently being introduced whereby the SVA MO concludes a framework agreement or supply contract centrally and hands it over for implementation to, for example, a logistics agency, which then places orders, invoices, and so on, within the framework of the agreement or contract. This frees up personnel capacity at central offices for the implementation of other required acquisitions.

How does the concept of army development and the defined alliance goals (CT) translate into the procurement system?

The concept of army development naturally reflects, among other things, the assigned alliance objectives, even though the document itself is only of a general nature and primarily sets out the capabilities that the army is to achieve within a certain time frame. Of course, achieving a certain capability almost always involves some kind of acquisition. The specific acquisition needs will be determined by the conceptual and analytical work of the relevant organizational units of the General Staff of the Czech Armed Forces in cooperation with other components of the Ministry of Defense. The identified acquisition needs must then be planned, first in a medium-term plan and then in a specific acquisition plan.

The SVA MO and other central procurement offices are then responsible for implementing these acquisitions, but they also have a role and tasks in the planning phase. In particular, we must assess whether the user's ideas about the scope, implementation deadline, delivery options, and financial cost estimates are feasible and realistic. At the same time, we must also set a deadline for receiving the specifications, i.e., the detailed requirements of the Czech Armed Forces, so that the acquisition can be completed within the required time frame.

This system has been in place for a long time, and we are now focusing mainly on digitizing it to speed up and simplify the process.

The resort is often criticized for its excessive prices, which do not reflect market reality. Do you conduct market research to ensure that the resort does not spend money unnecessarily?

Market research is an integral part of the specification for the required property; this is a basic rule applied within the Ministry of Defense. Another essential measure to prevent overpriced acquisitions is to assess the usual price, or market price, if possible by an accredited expert. The problem is that it is sometimes difficult to find such an expert due to the very specific nature of the material, in which case we have to resort to an assessment by an expert commission.

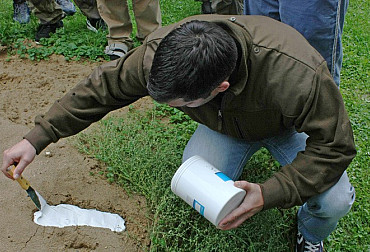

Unfortunately, criticism is often based on a lack of knowledge of the complexity of military procurement. We always try to procure material as a system, i.e., to purchase it as a functional whole, rather than buying individual components. Take small arms, for example. We purchase them in military specifications, as a system, i.e., with all accessories, including optics, sights, spare parts, armorer kits, and the like. This transfers the warranty, any complaint procedures, and the resolution of any problems to a single supplier, which simplifies the entire process and reduces the administrative burden. It also ensures that the system as a whole will be functional, the components will be interoperable, and the system will have the required tactical and technical characteristics. Since the supplier is usually not the manufacturer of all the required components, it assumes the risk for other manufacturers, and of course charges for this. From this point of view, a comparison of prices with the civilian market is not valid.

It is also important to realize that we are purchasing specific products for which there are only a limited number of suppliers on the market, or even just one, which also affects prices. Of course, the factors mentioned above that influence price increases also play a role.

It is not uncommon for us to cancel an order due to an unacceptably high bid price, but this has a significant negative impact on the required capabilities, as the army will not receive the necessary equipment in the required time.

The Ministry of Defense is often criticized for the fact that the final prices do not correspond to the originally estimated costs, for example. This may be due to many factors (price increases, etc.), but there are also situations where the user changes and expands their requirements during the negotiation process, among other things, in view of the experience of the war in Ukraine or in order to acquire the most modern and highest quality technology and materials.

Well, sometimes we simply have to accept the asking price because no one else will offer the material we need at a lower price.

Recently, there has been a lot of talk about the purchase of new field kitchens, which is often described as overpriced. Does your department have any other options for verifying the actual price?

Much has been said and written about field kitchens. I have heard opinions that someone could have put together such a kitchen for half the price. That may be true, but no one offered us such a price in the tender. Yes, the kitchens were not exactly cheap, but the lowest bid in an open tender was selected.

It is also important to realize that this was not a commercial product, of which there are several on the market from different manufacturers. The kitchen must meet the specified technical parameters, and the supplier must develop it in practice. It is up to the supplier to decide which components to use and from which subcontractors, but they must meet the required parameters. The supplier is also responsible for the overall functionality and provides a warranty for the kitchen as a whole.

In terms of price comparison, it is difficult to compare something that is not available on the market in the required specification and configuration and has not been purchased before. And as I have already mentioned, the Ministry of Defense had a choice: either to accept the offer resulting from the tender and purchase the necessary kitchens, or to cancel the order, in which case the army would be left without kitchens.